Part 3 - John S. O'Connor

American Brilliant Glass Education and Research - HBG

"Parisian" Pattern

This is the continuing story of an unknown pattern that has been attributed by several collectors and dealers to C. Dorflinger & Sons. Questions concerning this pattern — together with a couple of “close relatives” — have accumulated during the past fifteen years. The story, which really amounts to a mystery, is summarized in this file, together with evidence that is often conflicting. Red herrings also make their appearance.

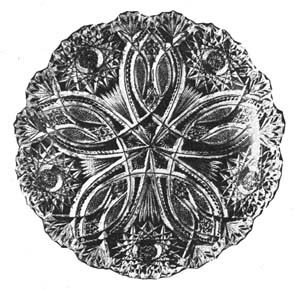

The ice-cream tray below was purchased at an antiques shop in coastal Connecticut on 6 October 1983. The owners, knowledgeable dealers in American cut glass, had bought it earlier while on a visit to Maine. With one minor variation, the pattern can be seen to match that on a “shallow 11-inch bowl” in AMERICAN BRILLIANT CUT GLASS, the first book on cut glass written by B. and L. Boggess (fig. 147, p. 112). The variation concerns the converging ribs of the fans. On the tray they converge to a point, but on the bowl this convergence includes an area that is cross-cut. There is no doubt, however, that the two items are from the same manufacturer and represent the same pattern.

Ice cream tray. Dorflinger shape no. 1040. Late nineteenth or early twentieth century. L = 15″ (38 cm), w = 10.75″ (27 cm), wt = 7.75 lb (3.5 kg). Sold in 1984 for $675 (Image: Bill Lauten)

Several months after the tray was purchased, an article appeared in Antiques & The Arts Weekly showing this exact pattern. This issue of 21 June 1985 also includes an announcement by the Fashion Institute of Technology (NYC) that it has recently acquired the “late nineteenth century” cut-glass ice-cream dish that is pictured below. It was donated to the Institute by Katheryn Hait Dorflinger Manchee (1904-1991) who at one time was married to William Dorflinger, a grandson of the founder of the Dorflinger glass company. The article contains no additional information about this item. An additional dish, of identical pattern and apparently of identical size, has been reported to be at the New Orleans Museum of Art. Manchee also donated this item, in 1986, when she told the museum that “The dish was part of a service reserved by Christian Dorflinger for his personal use.” (note 1).

In spite of the considerable amount of material that has been published about C. Dorflinger & Sons since 1985 no positive identification of this pattern has yet been made. The tray shown here appears to be cut on Dorflinger’s blank (shape) no. 1040; the blank used for the Boggess item could be Dorflinger’s no. 512. Unfortunately, published examples of Dorflinger blanks often lack dimensions, making positive identification uncertain.

A couple of developments have added more mystery to this story. A member of the American Cut Glass Association submitted a photograph to the association’s newsletter, The Hobstar, for the January 1995 issue in an attempt to seek “pattern and dating information on the Signed Fry illustrated Bowl.” The photo is none other than a duplicate photograph of the “shallow bowl” that appeared in the Boggess book and which originally had no signature! (Consider the Fry signature to be red herring no.1. Emmerson, in his article, has provided evidence that this Fry signature is bogus [see note 1].) Four months later this ACGA member was back with another photograph. This time the shape is the same, but the elaborate pattern — definitely a “close relative” of the mystery pattern — shows two significant differences: the cross-cut section of the fans has been replaced with prominent beading, and the motif of fine diamonds, contained within the twin vesicas on all of the examples mentioned above, has been replaced with the cane motif. There is no mention of a signature.

The plot of this mystery thickens a bit more, although some would consider the “evidence” to be no more than additional red herrings. The Boggesses in COLLECTING AMERICAN BRILLIANT CUT GLASS show an ice-cream tray identical to the one shown here except that the pattern has been rotated so that the twin vesicas — rather than the hobstars — occupy the two “handles”. The authors state that the tray is cut in the “Ducal pattern and signed Straus” (red herring no. 2). L. Straus & Sons did cut a pattern named Ducal, but this is not it (compare the image below, left). And Straus never signed its cut glass with an acid stamp. If the tray has an acid-etched star-in-a-circle — and we have only the Boggesses’ statement to this effect (note 2) — this indicates only that the blank is from the Libbey Glass Company.

Toward the end of their book the Boggesses again take up the mystery pattern, reproducing the photograph of the “shallow bowl” from their first book. This time around they imply that it was made by Dorflinger and state that it is “the same pattern as [Dorflinger’s] Sonoma except with a hobstar”. This is an odd statement because, as shown below, right, the Sonoma pattern is cut with hobstars! The Boggesses also show a plate or tray with pinwheels. It is another “close relative” of our mystery pattern, having by now the familiar double miters and beading. But it is a far cry from the Sonoma pattern (even allowing the substitution of pinwheels for hobstars) which is the name the Boggesses give it (Chalk up red herring no. 3). It would be a shame if a collector were to pay the relatively high price usually associated with the mystery pattern for an item that is actually cut in the Sonoma pattern. More importantly, the mystery pattern is an elegant example of late Victorian opulence; the Sonoma pattern, a stripped-down wannabe-on-a-budget.

LEFT: Ducal pattern on a 10″D salad bowl, shape no. 353, by L. Straus & Sons as shown in its catalog, L. STRAUS & SONS (1893), reprinted by the American Cut Glass Association in association with Smithsonian Institution Libraries (1987, p. 10). RIGHT: Sonoma pattern on an 11″l oval dish by C. Dorflinger & Sons, taken from an undated catalog reprinted in Feller 1988, p. 278. Copyrighted; used with permission.

Emmerson has also provided evidence that the cuttings on the ice cream tray and dishes may have been carried out by J. S. O’Connor’s American Rich-Cut Glass company. And this is no red herring! A bowl thought to be cut in the mystery pattern is shown in an ad from this company that appeared in the trade journal Jeweler’s Circular Weekly on 11 Aug 1897 (p. 11). The bowl only is shown here; the entire ad has been reproduced in Barbe and Reed (2003, p. 192) (note 3).

Relative to this bowl, Emmerson writes that he is “unaware of any other cut glass pattern having the exact motifs half way down the side of the bowl [which is all that one can see in the ad] and then turned out to not [emphasis original] be the mystery pattern.” This argument helped convince this writer that the mystery pattern was, indeed, cut by O’Connor’s shop.

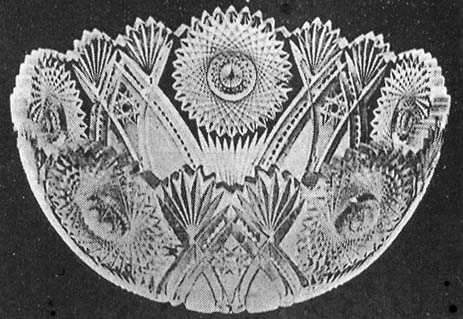

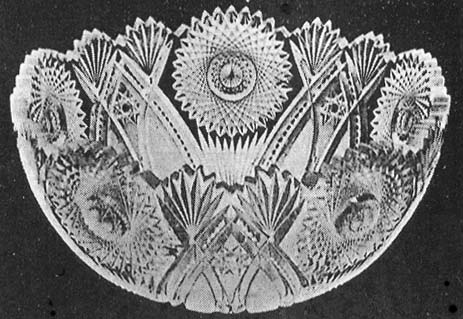

The illustrations below, recently acquired by the writer, show both the interior and the exterior of a punch bowl that appears to match the bowl in O’Connor’s ad. The double miters do not diverge toward the bottom of the bowl, and neither do they do this in what can be seen in the ad. In the mystery pattern, however, the double miters do diverge. As a result, the pattern of miters in the bottom (i.e., center) of the mystery pattern — see the first two illustrations in this file — is entirely different than the pattern similarly located in the punch bowl.

Note that the ad does not show the vertical miter cuts (“splits”) that are contained within the twin vesicas of the punch bowl. The writer believes that this was an option for the cutter, to be used to enhance the strawberry-diamond filled vesicas, if desired. It would have been especially appropriate on a bowl as large as this one; the bowl in the ad might have been smaller.

Two images of a punch bowl believed to have a pattern that is identical to the bowl shown in an ad from J. S. O’Connor’s cutting shop (see text). The second image shows a view of the bottom of the bowl taken on its cut side. D = 12″ (30.5 cm), H = 5.5″ (14.0 cm). Sold as the Venetian pattern by Hawkes — the seller is obviously not a cut-glass person — for $875 at an eBay auction in 2004. This was the starting bid; there was only one bidder (Images: Internet).

The writer believes that these new illustrations complete the partial view of the pattern that is shown in O’Connor’s ad. If this is true — and only time, with its additional evidence, will tell — then it follows that this O’Connor pattern is different than the mystery pattern. Because of its similarity, however, it is reasonable to call it “Vesica Variant” until its official name is discovered. Accepting the foregoing argument, it is concluded that the “Vesica Variant” pattern was made by J. S. O’Connor’s American Rich Cut Glass Company of Hawley, PA, at least as early as 1897.

If the “Vesica” pattern is a version of “Vesica Variant”, then it would also likely have been cut by O’Connor’s company. If, on the other hand, the “Vesica” pattern is not a version of “Vesica Variant”, then its origin continues to be unknown. Whichever statement proves to be the case — and the writer is betting on the first one — both patterns owe their existence to T. G. Hawkes’ Chrysanthemum pattern of 1890. Regarded by some investigators as marking the true beginning of the “brilliant style” in American cut glass, the Chrysanthemum pattern inspired derivatives, including patterns by T. B. Clark & Company and the J. D. Bergen Company, as well as O’Connor’s “Vesica”. The Hawley cutting shop also produced an even closer approximation of Hawkes’s Chrysanthemum pattern with one it called Crescent. It was cut in 1895, if not earlier.

NOTES:

1. Emmerson, Leigh, 2002: Another mystery solved??? Maybe!!!, The Hobstar, Vol. 24, No. 7, pp. 1, 10-13 (Apr).

2. Information provided in the books by Bill and Louise Boggess is often erroneous (see the boggess.html file in Part 1).

3. Emmerson introduces an unwelcomed note of ambiguity in his article because he indicates that the bowl in O’Connor’s ad is “an artist’s depiction”. It is not; it is a photograph.

No Longer a Mystery Pattern, It Is Now Identified as O’Connor’s Crescent

One-piece punch bowl by J. S. O’Connor. D = 14″ (35.6 cm), h = 7″ (17.8 cm), wt = 18 lb (8.2 kg). Offered for sale for $1,950 (plus shipping expenses) as a “buy it now” item on eBay, where the pattern — which is, in all likelihood the Crescent pattern — was incorrectly identified as Caprice, which is a different O’Connor pattern. The bowl was advertised during Oct/Nov 2008. Although the Crescent identification is not 100% certain, evidence in the paragraphs that follow these images indicates that this is the case (Images: Internet):

See CUT GLASS ADVERTISEMENTS, Book 3, by Smith and Smith (editors), 2003, p. OCJ-16 for an illustration of this pattern as it appeared in an ad placed in the journal Jeweler’s Circular. The pattern is not named in this ad, but the name is given in an article that appeared in the same publication the previous week (4 Aug 1897, p. 44). That article reads as follows:

A magnificent bowl of cut glass, 18 inches in diameter, was put on exhibition last week in the window of Jacot & Son’s store, 39 Union Sq., and attracted the attention of the crowds who promenade New York’s shopping district. The bowl is the product of the cut glass works of J. S. O’Connor, whose New York salesrooms are situated in the Jacot building. It is the finest piece of its kind turned out by this firm and is one of the largest cut glass bowls ever shown in New York. The decoration is an elaborate design known as the “Crescent” cutting.

This is not the first mention of the Crescent pattern. It is illustrated, on a pair of quart decanters, in a Jeweler’s Circular ad that O’Connor ran as early as 19 May 1897. In that depiction of the pattern, of which only the uppermost part is visible, the design is somewhat simpler: There is no beaded double-mitering. What seems to have happened is what happened to another O’Connor pattern at this time: The original 400 (“four hundred”) pattern was changed to “Improved 400”, most likely to reflect an elaboration of the original design. Unfortunately, we have no illustration of either the original or the “improved” pattern. One (or the other) is listed simply as “The 400” in a list of ten “Special Designs” that appears on the company’s letterhead that in use during the late 1890s. The Crescent pattern is also listed as one of these “Special Designs.”

Content courtesy of Warren and Teddie Biden and Jim Havens